original: http://www.hackernews.com/bufferoverflow/00/dosattack/dosattack.html

reprinted: http://www.digitalmogul.com/membersonly/articles/2000/02/xxx.html

french: http://www.hackzone117.com.bi/bufferoverflow/00/dosattack/dosattack.html

french: http://www.s0y0s.t2u.com/secu/doc/dos/dosattack.html

Have Script, Will Destroy (Lessons in DoS)

I began writing this article almost one year ago, after the onslaught

of smurf

attacks being launched against

various networks throughout the Internet. At the time, the newly

discovered Denial of Service (DoS) attack was a crippling tool designed

for one purpose; remotely disabling machines by flooding them with

more traffic than they could handle. The smurf attack was the

first well known (and well abused) DoS attack that could effectively

cripple any network, regardless of size or bandwidth. This presented

a new problem to network administrators and security personnel worldwide.

The LowDown

Also known as Network Saturation Attacks or Bandwidth Consumption

Attacks, the new breed of DoS

attacks flood a remote network with an staggering amount of traffic.

Routers and servers targeted would go into overdrive attempting to route

or handle each packet as it came in. As the network receives more and

more of these illegitimate packets, it quickly begins to cause legitimate

traffic like web and mail to be denied. In minutes, all network activity

is shut down as the attack consumes all available network resources.

Prior to bandwidth consumption attacks, most DoS attacks involved sending

very few malformed packets to a remote server that would cause it to crash. This

occurred because of bugs in the way many servers handled the malformed

packets. Malformed packets (also known as Magic Packets) consisted of network protocol options that were

out of sequence, improperly matched, or too large. As a result, a server

receiving these packets had no rules or guidelines dictating how it should

behave when processing the malformed packet. The result was a system panic

or crash that would basically shut the machine down or force it to reboot.

Perhaps the most well known example of this type of attack is the

WinNuke attack.

Regardless of ethics or motives, Magic Packet DoS attacks showed an inkling

of grace in their execution. A single packet sent from one server to another,

causing it to crash or reboot was a targeted attack. The precision with

which this type of attack is carried out is analogous to a scalpel in

surgery. Network consumption attacks on the other hand involve millions

of packets. Worse, once launched the attack was no respecter of those

standing between the launch point and the target network. Often times

thousands of customers sharing bandwidth with the target would be adversely

affected as well. A single attack of this nature had the ability to

knock thousands of machines off the Internet in a single swoop. Such

attacks are the equivalent of using a broadsword to do surgery.

The Next Generation

Attacks like the smurf DoS have a cascading affect that can

be seen as a virtual avalanche. The starting point is nothing more than

a few pebbles and snowballs (packets). As they travel downhill (along

the path of routers to the target), they accumulate more mass and trigger

the release of more pebbles. By the time the falling material hits

the bottom of the mountain (the target), it is swamped in large amounts

of snow and rocks. Despite the effectiveness of this attack, there is

a single point from which the attack is launched. If an attack is detected

early enough, it is possible to filter out the offending packets before

they leave the original network.

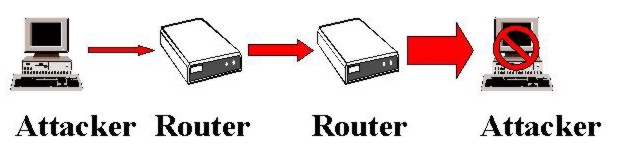

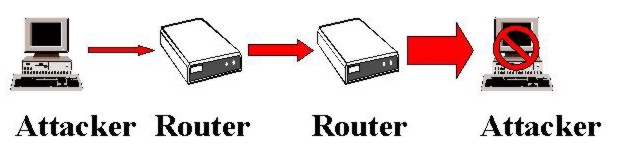

The next generation of Denial of Service attacks are known as Distributed

Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. Expanding on the idea of network

saturation attacks, DDoS effectively does the same thing but utilizes

several launch points. The philosophy and objective of this is twofold.

First, if a single machine being used to launch an attack is discovered

and disabled, the overall attack proceeds with near full force. Second,

by utilizing several launch points on different networks, an attacker is

able to shut down larger networks that might not otherwise be affected

by a single flood.

Taking Down the Big Boys

Prior to launching this form of DDoS flood, the attacker must first

compromise various hosts on different networks. The more networks and

machines

used as launch points, the more potent the attack. Once each host had been

broken into, they would install a DDoS client program on the machine that

would sit ready to attack. Once the network of compromised servers was

configured with the new client program, the attacker could send a quick

command from the DDoS server software triggering each machine to launch

an attack.

[chart comparing 56k vs cable vs t1 vs t3]

Until this last wave of DDoS attacks, it was generally assumed that

hosts residing on large pipes (connections with incredible bandwidth)

could not be seriously affected by network saturation attacks. As large

Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are finding out, this is no longer

the case. By using several smaller network connections, an attacker

can eventually saturate the biggest ISPs and consume all of their

bandwidth. This was demonstrated most effectively with the

three hour shutdown Yahoo,

and subsequent attacks against

eBay,

Amazon,

Buy.com and other large scale web sites.

Difficulty in Tracking

Neophytes to networking always seem to question why these attacks are

not tracked down, and the legs of the perpetrator not broken. It is a rare

case to see ISPs interested in tracking down the individual(s) behind

these attacks. Rather than take the time and effort to perform an

investigation (which is lengthy), most ISPs realize that a quick

filter denying ALL traffic to the site being attacked is a better

solution. In essence, the ISP does the job of the person launching the

attack and does it much more efficiently. As you can imagine, that is not

exactly a deterrent for those committing these attacks.

One of the primary reasons investigations of DoS attacks is lengthy

is it involves tracking down the packets hitting the target. Rather

than leave the launch point with the IP address of the machine actually

being used, the packets are tagged with forged source IP addresses.

Since the IP information in each packet varies wildly, and since the

addresses cannot be trusted, a network administrator must trace

the packets back to the source one router at a time. This involves

connecting to the router (often times this must be done at the physical

console for security reasons), setting up a filter or sniffer to detect

where the packets are coming from before arriving at that particular

router, and then move to the new offending router. This presents problems

when you consider a single packet may cross as many as thirty routers

owned by ten different companies.

The act of forging the source IP of a packet is called

IP Spoofing

and is the basis for a wide variety of network attacks. One of the original

intentions of a Denial of Service attack was to knock a machine off the

network in order for you to assume it's identity. Once you masquerade

as that machine, it is possible to intercept traffic intended for

it as well as gain access to other machines on the target network via

trusted host relationships. Attackers today seem to have lost all

focus on the reason one would committ a DoS attack.

Save The Day Already!

Denial of Service attacks are not new. They have existed in one

form or another since computers were invented. In the past they involved

consuming resources like disk drive space, memory or CPU cycles.

Those not familiar with how computers operate often scream for quick

solutions to the various DoS attacks that plague our networks. Unfortunately,

this is easier said than done.

Every weekday morning and afternoon millions of Americans go to and from

work. They pile on to two and four lane freeways only to move at a crawl.

Travelling ten miles in one hour is a common occurrence for those fighting

rush hour traffic in heavily trafficked areas of business districts in

cities across the nation. Every day they carry out this ritual, screaming

and cursing the thousands of other drivers clogging the roads, and day

after day the problem does not fix itself. Be it packets or cars, it

is very well established that enough of either will overcrowd a road

or network connection. At a given point, too many of either will bring

all traffic to a standstill. Why isn't the traffic problem solved?

We all know the solution is bigger and better roads, more carpooling,

diverse schedules, and more common sense when behind the wheel. Fat

chance that will happen anytime soon. On the flip side, it is very

unlikely that they will fix every router on every network and install

mechanisms to help avoid network saturation attacks.

In the long run, it is a rather simple fix that could help eliminate

these attacks. Any network device that accepts or passes network traffic

can be designed to monitor activity better. If a web server is receiving

too many hits, it starts rejecting new connections so that existing

connections can still view pages or interact with the site. This practice

is called throttling or bandwidth limiting

and is designed to prevent excessive connections,

conserve resources and keep things operating correctly. Unfortunately,

this philosophy has not carried over to routers (the machines that

pass all internet traffic) so network consumption attacks go on unchecked.

A relatively few amount of networks have learned this is a good solution

to flood attacks. As such, their routers are designed to monitor traffic

and quit passing illegitimate traffic once detected. The problem with

this approach is that once the flood of packets have hit the remote

network, the damage is done. The downside to this mechanism is the

added latency as the router checks each and every packet that passes

through it. Because of this slowdown, ISPs hesitate implementing this

solution.

In order to make connection throttling effective, every network router

should have this mechanism implemented. This would allow a router close

to the source of the attack to detect the illicit traffic and put up

a filter that rejected it before it left the launch point. This invariably

leads to the question "How do you know if traffic is illegitimate?"

Looking back to the section on IP spoofing, we can easily create a quick

solution to the problem. In fact, this mechanism is found in most Firewalls

implemented today.

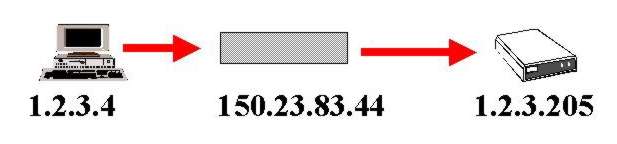

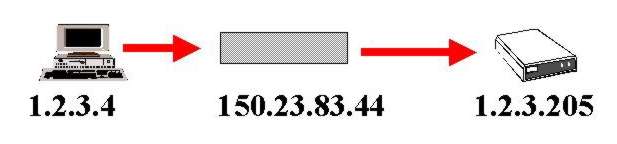

In the diagram above, we show a forged packet with the IP address of

150.23.83.44. It stands to reason that such a packet would not legitimately

be travelling around a network designated by the 1.2.3.x subnet. Because

of this, any router on that network (especially the one acting as a gateway

to the outside world) receiving that packet should drop it. Instead of

blindly passing the packet on without question, routers should discriminate

against suspicious packets by refusing to pass them on to the next router

and setting off some kind of alarm for the administrator.

A second mechanism can be put into place that would help cut down on

these attacks. On any given day, there is an average amount of traffic

passed through any router. By monitoring these averages and applying

other common sense rules, routers could be made to throttle heavily

increased traffic. For example, if a router detected a sudden surge

in traffic to a destination machine in which every packet claims to

originate from a different IP address, that is a good sign of a

saturation attack using spoofed packets. Rather than pass that traffic

down the network, the router should throttle the traffic to avoid

the likely flood that will ensue.

As stated many times before, easier said than done. Implementing

these features falls on the many vendors of routers. Using these

routers on production networks on the open Internet is up to the

tens of thousands of companies maintaining a presence on the Internet.

These upgrades cost time and money, something companies hesitate

to invest; until the first time they are on the receiving end of

such an attack. Like most security incidents, companies tend to implement

reactive security measures, rarely proactive measures.

Why Ask Why?

Somewhere along the way, everyone wants to know why such attacks

are carried out. Using the recent series of attacks against Yahoo,

eBay and others is just as good example as any. To quash the distant

hopes of a reasonable explanation, "There is no good reason!".

Consider that your typical DDoS attack affects hundreds (if not

thousands) of machines, on a wide variety of networks. The single

purpose of the attack is to cripple or shut down the target site

so that it can not receive legitimate traffic. There are only a handful

of reasons for doing it at all, none of which are reasonable or

justifiable. In other words, DoS attacks are worthless and childish.

The first reason with perhaps the longest history is simple revenge.

Some site out there wronged you in some way. Perhaps they spammed you,

stopped hosting the free web pages they provided for you, fired your

father or committed some other transgression. DoS attacks are a form

of virtual revenge, especially against companies doing business over

the Internet. The primary argument here is that these attacks cause

problems for a number of ISPs, other customers who share bandwidth

with the target, as well as the satisfied customers of the site. This

goes back to the broadsword vs scalpel analogy.

The second reason has become rather trendy with novice script kiddies, second rate

web page defacers, and those under the illusion they are part of the

professional security community. "I did it to prove the system

was vulnerable!" This is perhaps the most pathetic justification for

launching a DoS attack. To many, this is no different than the attacker

setting off a large nuclear device right next to a corporate server

and then proclaiming "See! This can impact your operations!"

Of course it can, this has been proven a hundred times over.

The third reason I can come up with falls back to playground rules.

"If I can't play kickball, I'll throw the ball on the roof so no one

else can play either!" This third grade mentality is far from

justification of such attacks. Those wishing to exact some form of

punishment against a site should consider the diminished intellect

required to launch these attacks. There are better ways to deal with

mean companies.

My Rant

Three types of people deserve the brunt of harsh insults and petty

name calling. Each are responsible for this problem plaguing

Internet users, and each could do their part to help stop it.

Each individual that carries out a DoS attack does so knowing full

well what it could result in if they are caught. Practically nothing.

There is precious little to deter someone from carrying out

such vicious attacks. The very few times administrators put effort into

tracking down a malicious user it results in them getting ousted from

the ISP. The next day, the offending user is back online accessing the

Internet via another ISP. Until the attack against Yahoo, the Federal

Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was not concerned over these attacks.

To date, the FBI has not managed to apprehend the perpetrator of a

devastating DoS attack against their own home page (www.fbi.gov).

For one reason or another they were seen as an annoyance, not a reason

for loss of business. Law Enforcement needs to take a bigger interest

in DoS attacks and start to punish those responsible. These types of

attacks should take any competent law enforcement agent a few hours of

tracking and maybe a handful of legitimate warrants.

Like the FBI, ISPs receiving these attacks need to take more proactive steps

in preventing DoS attacks. When they do occur, ISPs should also take more

time in tracking down the offending users and passing on the information

to appropriate law enforcement. Rather than silently kicking them off

the Internet for a day, taking a more active and public stance showing

that malicious activity will not be tolerated would have a better

effect. Those ISPs scared of retaliation need to remember that they

are in the best position to stop the attackers.

Last, the pathetic kids (literally and figuratively) committing these

attacks. In many cases, these attacks are launched with mystical scripts

written in foreign languages and just produce the desired affect. There

is no grace, no skill, and no intellect behind these attacks. You are not

a hacker and you do not deserve respect for your childish actions.

You are no better than the twisted individuals who spray a crowd

of innocent bystanders with a machine gun, only to nick your intended

target. If you can't express yourself better than a saturation attack,

and can't deal with being called a name or wronged somehow, seek help

offline. You sorely need it.

Article: Brian Martin (bmartin@attrition.org)

Images: Dale Coddington (dalec@attrition.org)

http://www.attrition.org

Copyright 2000 Brian Martin